Q fever is a zoonotic disease. This means that Q fever, which is an animal disease, can also infect human people. Many animal species are susceptible to Q fever, but the most concerned species are ruminants, including cattle, sheep and goats.

How people get infected by Q fever?

In ruminants, the main clinical signs are reproductive disorders including abortions, stillbirth, metritis and retained placenta. Consequently, vaginal discharge, aborted fetuses and fetal annexes can contain many bacteria and are therefore considered as the main virulent materials.

Coxiella burnetii, the bacterium responsible for Q fever, is also shed in feces and in milk. Manure is therefore also an important virulent material. Conversely, milk is of lesser risk as the risk of contamination through milk consumption is considered as negligible.

As the route of contamination for animals and people is airborne, bacteria spread from virulent material left on the ground and subjected to air currents. This is particularly the case when placentas are left in the litter or when manure is spread in windy conditions. As the bacteria are very small, they can be carried by the wind easily up to 18 km.

People at particular risk of being infected with Q fever are therefore people working in contact with animals (such as farmers, veterinarians, inseminators, slaughterhouse workers, etc.) and people living near infected farms.

Q fever is therefore a very contagious disease for exposed people.

Clinical signs of Q fever in humans

Unlike ruminants, the clinical pattern of Q fever in humans is not dominated by abortions.

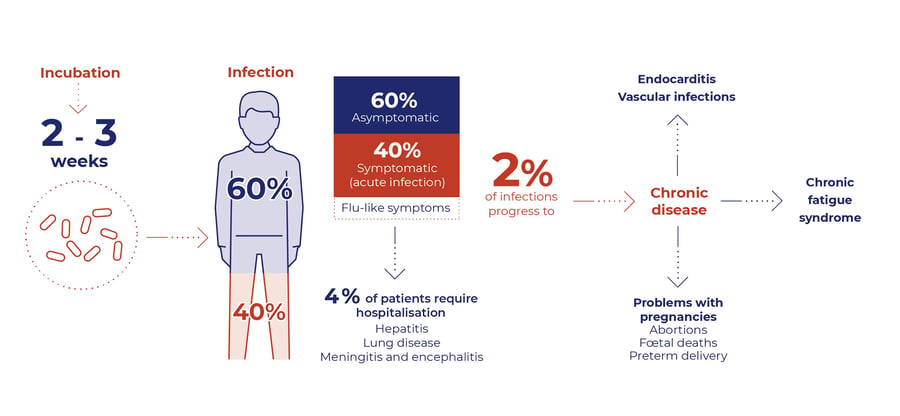

In most cases (60%), Coxiella burnetii infection is even asymptomatic. In the remaining 40% of cases, the infection is characterized by a flu-like syndrome. Nevertheless, 4% of patients require hospitalization due to hepatitis, lung infection, meningitis or encephalitis. This acute form of the disease mainly concerns immunodepressed people.

2% of Q fever infection will progress to a chronic form, which manifests itself as cardiovascular disease (endocarditis or vascular infection), chronic fatigue or for pregnant women abortion or premature delivery.

Therefore, although in most cases Q fever is a mild disease, the risk of hospitalization and the risk of chronicity mean that Q fever should be considered a serious disease and preventive and biosecurity measures should be taken.

Major outbreaks of Q fever in humans

According to the latest European Union One Health Zoonoses Report published in November 2021, 523 cases of Q fever in human were confirmed in European unit. Even if this figure seems to be low, it should be put in perspective because:

- many infections are asymptomatic or with mild clinical signs (flu-like syndrome). We can therefore assume that the number of cases is largely underestimated.

- 5 people died in 2020 in Europe because of Q fever

Collective cases of contamination occur regularly. Most of them remain limited to a few people as was the case, for example, in Australia in 2014-2015 (14 people confirmed in 4 months) or in France in 2017 (11 cases confirmed in 2 months).

But sometimes the event can last much longer and infect many people. The largest collective episode of human Q fever ever described occurred in the Netherlands between 2007 and 2010. A total of 4 026 cases were reported, of which 2 354 were in 2009 alone.

The origin of the human contamination was found to be sheep and goat farms. Collaboration between public health and veterinary authorities allowed the epidemic to be contained through the implementation of biosecurity measures and animal vaccination.

The zoonotic risk of Q fever is therefore of major importance. A good knowledge of the risk factors and a proper management of the farm regarding the disease by biosecurity measures and animal vaccination is crucial to avoid people contamination, especially when immunodepressed people or pregnant women work on the farm. This risk must also be considered when the farm receives visitors.

About the author

Philippe Gisbert (Ruminants Global Technical Manager)

Philippe Gisbert started his career in 1994 as a Vet practitioner working with companion and farm animals for over 9 years. He then became Health Affairs Manager for Group Agena (artificial insemination company). In 2008 he joined Eurofins – Laboratoire Coeur de France as Animal Health Unit Manager where he worked for 7 years until he joined Ceva France as Technical Manager Ruminants (Infectiology, Vaccines and Diagnostic). Since 2020 he is Global Technical Manager for Biologicals, Udder Health and Antiinflammatories. He is a member of SIMV diagnostic and anti-infective technical groups and has integrated different working groups of ANSES and UNCEIA related to epidemiology, antibiotic resistance and reproduction in livestock.

Explore author’s articles

%20(1)%20(1)%20(1).webp)

Leave your comments here