Pain is a normal defence reaction of the body. It is in fact an alarm signal for the animal in the event of “aggression” and triggers a serious of physiological reactions aiming to suppress or attenuate the attack, and thus minimise the negative effects. The effective management of this pain involves the use of veterinary NSAIDs (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs), playing a crucial role in ensuring the overall well-being and productivity of production animals.

However, when the pain is too severe (in intensity or duration), unnecessary, or when the measures to reduce it that the animal itself has put in place are insufficient, it becomes a negative element. Indeed, its effect on the animal's well-being becomes distressful and is no longer acceptable. Moreover, poor well-being impacts the animal's ability to express its full potential. In other words, pain is responsible for reduced production (milk and Average Weight Gain).

The management of pain in production animals therefore has a two-fold interest. Firstly, it is of ethical interest: it is essential to do everything possible to ensure the best possible welfare for the animals under our care. Secondly, there is a zootechnical interest: an animal that suffers produces less and is therefore less efficient economically.

Pain expression in cattle

Unlike other animal species, cattle generally show few signs of pain. For some diseases, such as lameness or acute mastitis, pain is visible (difficulty in moving, strong reaction of the animal to the touch, less support on a limb). But for others (respiratory disease, metritis…), the signs of pain are discrete and only a trained farmer who spends the necessary time observing his animals can identify them.

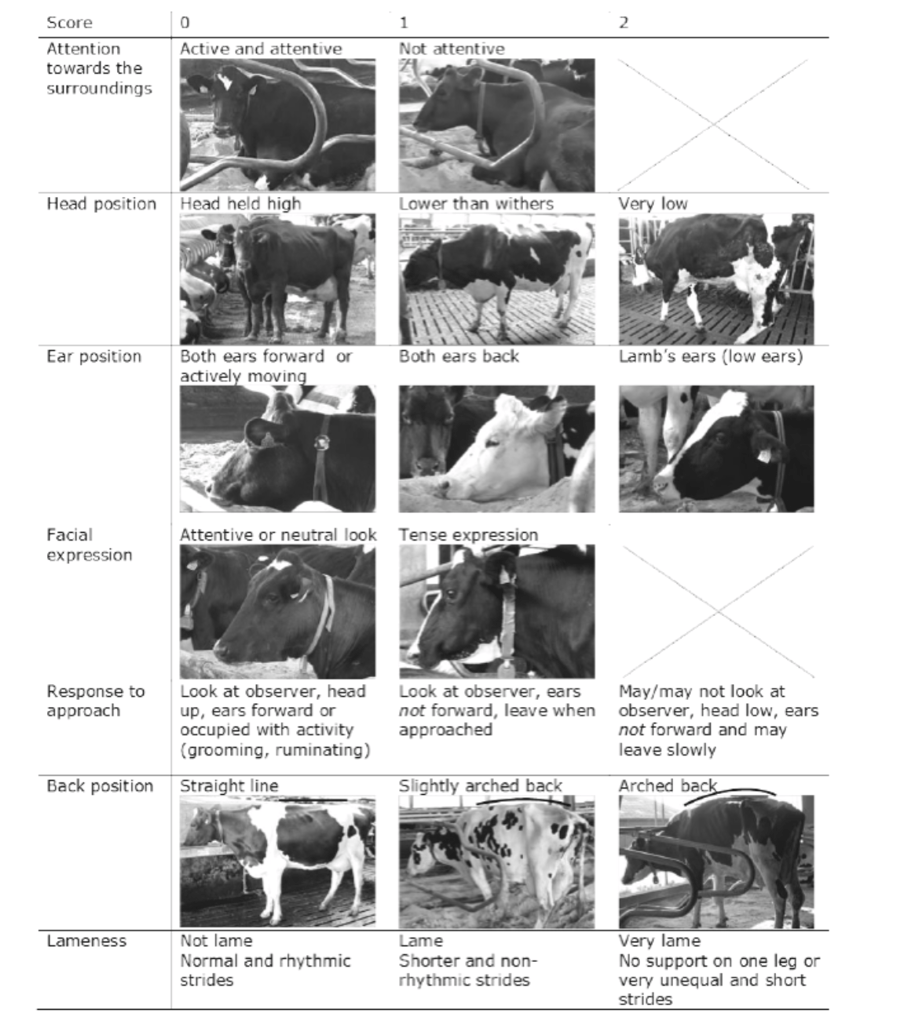

A few years ago, Karina Bech Gleerup proposed a description of the behavioural changes in dairy cows when experiencing pain (Gleerip et al., 2015; Gleerup et al., 2017). A scale that has been named by its authors the "Cow Pain Scale" (figure 1), evaluates and scores behaviours of the animal that has been associated with pain.

This scale shows that pain in dairy cows is expressed as:

- Attention toward the surroundings

- Head position

- Ear position

- Facial expression

- Response to human approach

- Back position

In cases of lameness, a criterion on stride length when walking is added to the cow scale.

Figure 1. The Cow Pain Scale (Gleerup 2017 in WCDS Advances in Dairy Technology (2017) Volume 29: 231-239)

Figure 1. The Cow Pain Scale (Gleerup 2017 in WCDS Advances in Dairy Technology (2017) Volume 29: 231-239)

Economic impact of pain in dairy cows

Beyond the animal welfare aspect, pain has also a cost. From a physiological point of view, pain causes stress, which is characterised by a release of cortisol from the adrenal glands. Cortisol has an immunosuppressive effect and therefore makes animals more susceptible to secondary infections. Similarly, pain causes a decrease in the secretion of luteinising hormone (LH). This leads to a decrease in fertility. Finally, an animal that is in pain moves less (it goes to the feed trough less) and has a reduced appetite; its production is therefore negatively affected by the pain.

Several technical and economic studies have highlighted the loss of animal production. For example, in cases of lameness, the reduction in feed intake has been estimated at 3 to 16% depending on the severity. As a result, milk production can decrease by up to 36%. In addition, there is a deterioration in fertility and a higher risk of culling. A review found that a case of lameness cost between 100 and 300 Euros (Ózsvári, 2017).

Calving, especially if it is dystocic, is also a painful experience for both cow and calf. Recent studies have shown that untreated postpartum pain resulted in a decrease in milk production of 611 kg over the first 305 days of lactation (Gladden, 2021). Similarly, untreated cows tended to conceive 22 days later than treated animals. For the calf, medical management of pain induced by assisted calving resulted in a higher Average Daily Weight Gain to weaning (+0.1kg/day). Female calves treated in this way were seen in heat earlier and, as a result, were bred at a younger age.

Control of pain in dairy cows

Pain management in dairy cows is therefore important. But before initiating treatment, it is essential to assess the intensity of the pain. Obviously, if the animal is in distress and expresses this through loud vocalisations or extreme isolation, it is easy to conclude that the pain is severe and therefore appropriate management, including veterinary intervention, should be considered without delay. In the majority of cases, however, the pain is more difficult to identify and the use of the Cow Pain Scale (Figure 1) is useful. Each criterion is given a score from 0 to 2, depending on the case, and it is accepted that a total score higher than 3/10 (without including the lameness score) or higher than 5/12 (with the lameness score) is considered suggestive of pain and necessitating a thorough clinical examination to check for the presence of a potentially painful condition.

Following this assessment and the decision to treat, it is necessary to determine which medication or other measures should be implemented. In 2009, the BOREVE group in France established three levels of treatment according to the type of pain and its intensity.

Level 1 can be managed by the farmer himself with the veterinary NSAIDs available to him. If the pain is assessed as level 2 or 3, a call to the veterinarian for management of the animal is necessary. At the breeder level, several veterinary NSAIDs may be available. Not all of them have the same pharmacological properties and therefore the most appropriate drug to deal with a particular situation should be discussed with the veterinarian. However, for lactating dairy cows, an NSAID that has a zero-milk withdrawal period, such as ketoprofen, may be very useful as a first line treatment, particularly when the pain is not related to an infectious process requiring an antibiotic. In this case, the pain can be treated without discarding the milk. The use of such a drug will relieve the pain of the animal without penalizing the farmer, since the milk produced can continue to be delivered for human consumption.

Conclusion

Even if the signs of pain expressed by cattle are sometimes weak, this does not mean that they are not suffering. It is therefore important to know these signs to correctly identify and interpret them. This will allow the implementation of adequate pain management that will benefit the animal first and foremost. But the farmer will also benefit because, in addition to the satisfaction of having responded to the animal's distress, he will improve the profitability of his farm. Through responsible pain management, including the use of veterinary NSAIDs, farmers can ensure both the welfare of their cattle and the economic efficiency of their operations.

References

Gladden, N. L. (2021). Bovine parturition: welfare and production implications of assistance and ketoprofen analgesia (Doctoral dissertation, University of Glasgow).

Gleerup, K. B., Andersen, P. H., Munksgaard, L., & Forkman, B. (2015). Pain evaluation in dairy cattle. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 171, 25-32.

Gleerup, K. B., Forkman, B., Otten, N. D., Munksgaard, L., & Andersen, P. H. (2017). Identifying pain behaviors in dairy cattle. WCDS Adv Dairy Technol, 29, 231-239.

Ózsvári, L. (2017). Economic cost of lameness in dairy cattle herds. J. Dairy Vet. Anim. Res, 6(2), 283-289.

About the author

Philippe Gisbert (Ruminants Global Technical Manager)

Philippe Gisbert started his career in 1994 as a Vet practitioner working with companion and farm animals for over 9 years. He then became Health Affairs Manager for Group Agena (artificial insemination company). In 2008 he joined Eurofins – Laboratoire Coeur de France as Animal Health Unit Manager where he worked for 7 years until he joined Ceva France as Technical Manager Ruminants (Infectiology, Vaccines and Diagnostic). Since 2020 he is Global Technical Manager for Biologicals, Udder Health and Antiinflammatories. He is a member of SIMV diagnostic and anti-infective technical groups and has integrated different working groups of ANSES and UNCEIA related to epidemiology, antibiotic resistance and reproduction in livestock.

Explore author’s articles

Leave your comments here