Bovine parasitic bronchitis or cattle dictyocaulosis is a disease of the upper respiratory tract caused by Dictyocaulus viviparus and characterized by a hacking, persistent cough and respiratory distress. It is especially common in calves from humid regions during their first grazing season1. Lungworms also represent an important issue in lactating cows. The costs associated with an outbreak of lungworms in cattle have been estimated at €170-300 per cow, with milk production losses averaging 4 kg/cow/day2. Subclinical disease can also contribute to decrease milk productivity, with estimated losses of 0.5 to 1.6 kg/cow/day3,4.

In addition to being unpredictable, clinical outbreaks are explosive with significant mortality and morbidity ranging from 6% to 100%5,6. While a vaccine has been available in some markets for over 60 years and anthelmintics are considered effective, lungworm disease continues to pose a serious threat to both animal welfare and income on dairy farms worldwide as the number of outbreaks has remained high 6.

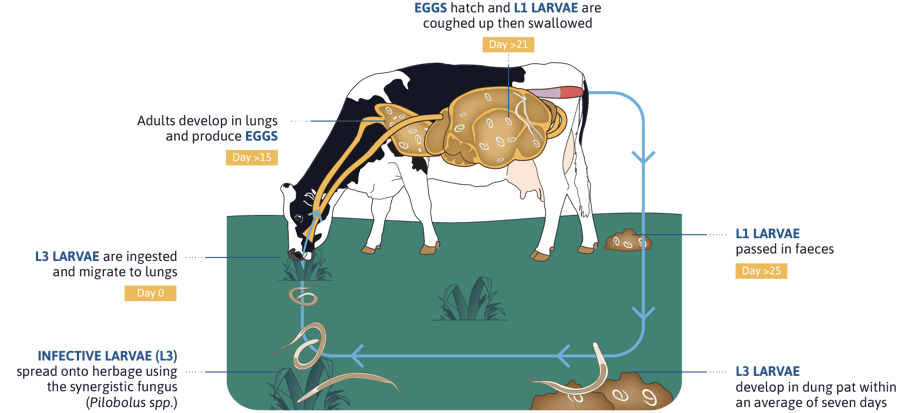

Life cycle

Adults are located in the bronchi and trachea; eggs hatch and first stage larvae (L1) are coughed up, swallowed and finally eliminated in faeces. In the environment, the L1 develops into a third stage larva (L3). Cattle get infected after ingestion of L3; after an internal migration and moulting, L4 reach the pulmonary alveoli and migrate to the upper respiratory tract (main bronchi and trachea) where they develop to L5 and adults. Female adults start to shed eggs 21-25 days after infection (prepatent period), lasting 4-6 weeks. Larvae can survive the winter as hypobiotic stages in the lungs (L4 or L5 stages), resuming their development in the spring and providing an important source of contamination for the next grazing season7.

Steps of the clinical disease

Lungworm disease usually occurs in late summer or early autumn. Clinical signs can be gradual or severe (death within 24-48 hr) depending on the parasite burden and the immune status of the animal. Clinical signs often start during prepatent period, that is before faecal test turns positive. Post-treatment signs will often persist in severely infected animals for 1-2 months. Three major phases can be distinguished in the development of the disease9,10:

- Prepatent phase (7-25 days post-infection): L4 larvae arrive to the alveoli, bronchioli and bronchi causing alveolitis, bronchiolitis and bronchitis. In severe infections coughing increases slowly until becoming widespread during the second and third weeks after infection. Heavily infected animals can present interstitial emphysema and pulmonary oedema leading to dyspnoea that can be fatal.

- Patent phase (26-60 days post-infection): adult lungworms are present within bronchi, causing parasitic bronchitis; in addition, the aspiration of eggs and L1 into the alveoli can lead to parasitic pneumonia. Coughing is the most common clinical sign; mildly affected animals cough intermittently, particularly when exercised, while moderately affected animals cough even at rest. Other common signs are tachypnoea, dyspnoea, nasal discharge and salivation. Some animals can show anorexia, dehydration, emaciation and fever.

- Postpatent phase (61-90 days post-infection): animals partially eliminate the lungworms and clinical signs disappear gradually; nevertheless, complete return to normality may take weeks or months due to the inflammation and/or fibrosis of bronchi. Some heavily infected calves can present a clinical syndrome called ‘postpatent parasitic bronchitis’ characterized by severe respiratory signs leading to death.

|

Phase & days post-infection (p.i) |

Dictyocaulus live cycle | Pathogenesis | Clinical signs |

|

Penetration phase 1 to 7 days p.i. |

Larvae penetrate the intestines and migrate to the lungs | No clinical significance | None |

|

Prepatent phase 8 to 25 days p.i. |

L4 enter into alveoli | Larvae in lower airways, inflammation Around day 15 start to migrate into bronchi |

Coughing begins, often with exercise, reduced milk yield |

|

Patent phase 26 to 60 days p.i. |

Mature adult worms in bronchi and trachea producing eggs |

Parasitic bronchitis: Worms and frothy mucous in upper airways Parasitic pneumonia: Collapsed areas around infected bronchi caused by aspiration of eggs and L1 |

Productive cough, weight loss, anorexia, laboured and fast breathing, reduced milk yield |

|

Post-ptent phase 61 to 90 days p.i. or after treatment |

Recovery phase after adult worms expelled |

Inflammed lung tissues, dissolution and aspiration of dead and dying worm material |

Persistent coughing, laboured breathing |

Identifying risk factors

Cattle lungworms are distributed worldwide and can affect both dairy and beef herds; nevertheless, the risk of infection is higher in:

- Grazing cattle

- Moist temperate regions or conditions (wet summer for example)

- Heavy stocking densities

- Animals with insufficient protective immunity. These animals are especially susceptible to get heavily infected and, consequently, show clinical signs. This explains why the clinical disease is common in calves during their first grazing season; in return, these animals are high shedders and thus, important contributors to pasture contamination8.

Key takeaways

- Bovine parasitic bronchitis is a worldwide distributed disease affecting first season grazing cattle and lactating animals in moist temperate regions.

- Infections can lead to substantial economic losses, due to mortality, reduced weight gain, milk losses and treatment costs.

- To build up a protective immune response, young animals should be regularly exposed to lungworms.

- Diagnostic tools are essential to confirm the clinical diagnosis and must be triggered as early as possible.

References

1. Deplazes, P., Eckert, J., Mathis, A, von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G. and Zahner, H. (2016): Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine. Wageningen Academic publisers, The Netherlands.

2. Holzhauer, M., van Schaik, G., Saatkamp, H.W. and Ploeger, H.W. (2011). Lungworm outbreaks in adult dairy cows: estimating economic losses and lessons to be learned. Vet Rec. 169 (19): 494-508. https://www.doi.org/10.1136/vr.d4736

3. Charlier, J., Ghebretinsae, A., Meyns, T., Czaplicki, G., Vercruysse, J. and Claerebout, E. (2016). Antibodies against Dictyocaulus viviparus major sperm protein in bulk tank milk: Association with clinical appearance, herd management and milk production. Vet Parasitol. 232, 36–42. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.11.008

4. May, K., Brügemann, K., König, S. and Strube, C. (2018). The effect of patent Dictyocaulus viviparus (re)infections on individual milk yield and milk quality in pastured dairy cows and correlation with clinical signs. Parasites & vectors 11(1): 24. https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2602-x

5. David G. P. (1997). Survey on lungworm in adult cattle. Vet Rec. 141(13): 343–344.

6. Ploeger, H.W. (2002): Dictyocaulus viviparus: re-emerging or never been away?. Trends Parasitol. 18(8):329-332. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/s1471-4922(02)02317-6

7. Bowman, D. (2014). Georgis' Parasitology for Veterinarians. ELSEVIER Saunders, Riverport Lane, Missouri, USA.

8. COWS. Control of lungworm in cattle. https://www.cattleparasites.org.uk/app/uploads/2018/04/Control-of-lungworm-in-cattle.pdf

9. Taylor, M. A., Coop, R. L. and Wall, R.L. (2016). Veterinary Parasitology, 4th Edition. Wiley-Blackwell. Garsington Road, Oxford, England.

10. Panciera, R.J., Confer, A.W. (2020): Pathogenesis and pathology of bovine pneumonia. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 26(2):191-214. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.cvfa.2010.04.001

11. Fiedor, C., Strube, C., Forbes, A., Buschbaum, S., Klewer, A. M., von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G. and Schnieder, T. (2009). Evaluation of a milk ELISA for the serodiagnosis of Dictyocaulus viviparus in dairy cows. Vet Parasitol. 166(3-4), 255–261. https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.002

About the author

Damien Achard (Ruminants Global Technical Manager)

Seasoned veterinarian, graduated from Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire de Nantes (France). After three years as a practitioner in central France, he pursued specialization in large animal internal medicine, completing an ACVIM residency and a Master of Sciences at the University of Montréal (2010-2014). Joining Semex Alliance as Health Manager for an IVF unit (2015-2016), he then transitioned to Ceva in 2016 as a Ruminants Global Technical Manager. Dr. Achard is an accomplished researcher, publishing on topics like downer cows, calf pneumonia or cryptosporidiosis and their associated therapies, and rational use of anthelmintics in ruminants. His ResearchGate profile (https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Damien-Achard/research) highlights his significant contributions to the veterinary field.

Explore author’s articlesAbout the author

Pablo Díaz is a Lecturer at the Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Spain. He graduated and earned his PhD in Veterinary Science from the Universidade de Santiago de Compostela (1999 and 2006). His research is focused on the epidemiology, diagnosis, control and prevention of parasitic infections of wild and domestic animals. His research career comprises 104 papers in JCR-indexed journals (H-index of 21), including 63 Q1 publications, more than 40 articles in professional magazines as well as more than 240 communications to both National and International Scientific Conferences.

About the author

Susana Remesar (Assistant professor at USC)

Susana Remesar Alonso is an assistant professor at the Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Spain. She completed her studies in Veterinary Medicine in 2015 and her PhD in 2019 at the Department of Animal Health of the University of Santiago de Compostela. Her research focuses on the parasitic diseases of animals, especially the study of ticks, their phenology, and tick-borne pathogens. She currently publishes the blog “Vetgraph: Medical & Veterinary Illustration” including illustrations about veterinary medicine, mainly related to parasites.

%20(1)%20(1)%20(1)%20(1).webp)

Leave your comments here