Clostridia are small anaerobic bacteria (living and growing in the absence of oxygen). They are found in the environment and in many animal species. The best known, because they are extremely dangerous, are Clostridium tetani and Clostridium botulinum, which cause tetanus and botulism respectively.

In ruminants, another bacterium, Clostridium perfringens, can cause enterotoxaemia, which in most cases is a superacute disease that leads to the death of affected animals within a short period of time. This disease mainly affects calves and young cattle fed to reach a high Average Weight Gain (AWG).

Clostridium perfringens type A is a commensal but dangerous clostridia

Clostridium perfringens type A is a bacterium normally present in the digestive tract of ruminants (cattle, sheep and goats). Its presence is therefore not abnormal.

Furthermore, this clostridia produces a major toxin called alpha toxin. It is this toxin that is responsible for enterotoxemia. In a normal state, the population of Clostridium perfringens type A in the small intestine is limited (less than 100,000 bacteria per g), so the amount of alpha toxin produced is limited. However, when conditions are favorable for its multiplication, the amount of this clostridia in the gut can reach 10,000,000 bacteria per g or even more. The amount of alpha toxin produced then becomes very high. If the animal's immune system has not been stimulated by preventive vaccination, enterotoxaemia can develop and lead to death.

Why does the clostridia responsible for enterotoxemia trigger the disease?

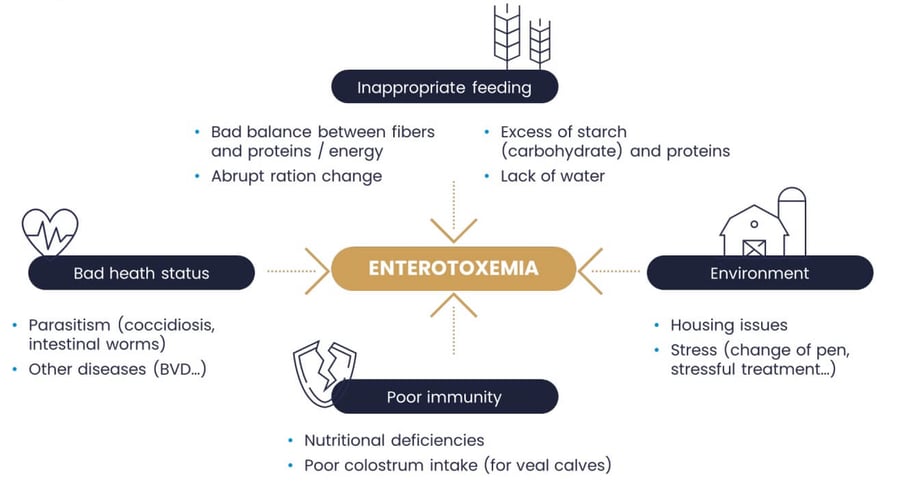

There are many factors that can cause the abnormal proliferation of Clostridium perfringens type A and therefore the high production of alpha toxin. However, they can be divided into two categories:

- Factors that cause decreased immunity: decreased ability of the immune system to maintain equilibrium and to neutralise alpha toxin

- Factors that promote the proliferation of clostridia in the gut.

Let's first look at the factors that lead to a decrease in immunity:

- Any stress, via the increase in cortisol production by the body, has an immunosuppressive effect. Stress can have various origins, but in cattle farming, the most frequent causes are linked to housing (overcrowding, change of pen, poor hygiene, etc.) or to excessive or stressful handling of the animals.

- Health causes: a herd where an immunosuppressive infectious disease such as BVD is present has a greater risk of triggering an outbreak of enterotoxaemia. Similarly, intestinal parasitism has a negative effect on the immune system.

- Finally, low immunity may be related to nutrient deficiencies (minerals, trace elements, vitamins) or, in young calves, to insufficient colostrum intake during the first hours of life.

The factors that encourage the multiplication of clostridia are essentially related to feeding. In particular, it has been proven that an excess of carbohydrates (starch) in the diet favours the multiplication of clostridia and leads to a decrease in the secretion of intestinal mucus, thus helping the action of the enzymes produced by the pathogenic clostridia. This is also favoured by stress and intestinal parasitism.

The figure below summarises the different causes of enterotoxemia:

Figure 1: The different causes of enterotoxemia

What are the consequences of enterotoxaemia?

Due to the rapid multiplication of clostridia and the mode of action of the alpha toxin, enterotoxemia is a very rapidly evolving disease. Indeed, the time between the onset of the first signs and the death of the animal is usually no more than a few hours. Therefore, it is not uncommon for a farmer to find one or more dead animals without having previously realised that some of them were ill.

One of the characteristics of the disease is that it usually affects several animals simultaneously. Indeed, when a feeding error occurs, it affects the whole group of calves or young cattle. It is also important to know that fast-growing animals, because of their ability to eat more, are more at risk than slower growing animals. For example, in a group of young cattle, it is often the best conformed that die the most.

The economic consequences of an outbreak of enterotoxemia in a feedlot are therefore very heavy and can reach several thousand euros.

How to control enterotoxemia ?

Although clostridia are bacteria, any antibiotic treatment is illusory. Firstly, the disease is due to the toxins produced, not the bacteria themselves, and secondly, once the first clinical signs appear, it is too late to act.

The control of enterotoxemia can only be preventive. This prevention has two components:

- Sanitary measures

- Medical measures

Sanitary measures are linked to the control of factors that can trigger the disease. Thus, managing the feed by being very strict about the amount of starch in the ration is one of the best ways of limiting the incidence of enterotoxemia in a farm or feedlot. Measures to limit animal stress or to maintain good immunity are also important.

In addition to these sanitary measures, vaccination with a vaccine containing alpha toxoid is effective. If the vaccination protocol is followed correctly, the level of antibodies capable of neutralising the alpha toxin will be higher than in unvaccinated animals and, consequently, these animals will be better able to resist an abnormal proliferation of clostridia.

Key message

Enterotoxemia, a disease related to the abnormal proliferation of certain clostridia in the gut, is a major problem in calf and young cattle rearing. However, it is well known and, even if no treatment is efficient, control measures exist to reduce or even eliminate the risk of such a disease appearing on a farm. The combination of sanitary and vaccination measures has for many years proved to be effective.

About the author

Philippe Gisbert (Ruminants Global Technical Manager)

Philippe Gisbert started his career in 1994 as a Vet practitioner working with companion and farm animals for over 9 years. He then became Health Affairs Manager for Group Agena (artificial insemination company). In 2008 he joined Eurofins – Laboratoire Coeur de France as Animal Health Unit Manager where he worked for 7 years until he joined Ceva France as Technical Manager Ruminants (Infectiology, Vaccines and Diagnostic). Since 2020 he is Global Technical Manager for Biologicals, Udder Health and Antiinflammatories. He is a member of SIMV diagnostic and anti-infective technical groups and has integrated different working groups of ANSES and UNCEIA related to epidemiology, antibiotic resistance and reproduction in livestock.

Explore author’s articles

%20(1).webp)

Leave your comments here